digital humans

a deep dive into representing and understanding humans

With the rapid advancement of technology, interactions between humans and machines have continued to skyrocket. And whether it’s asking ChatGPT for assistance or taking a ride in an autonomous vehicle, society has seen the remarkable impacts of deep learning (albeit often with undesired consequences, but that’s a discussion for another time). For many of these applications, AI algorithms must obtain a rich understanding of human language, appearance, and behavior in order to produce meaningful results. As you can imagine, humans are incredibly diverse, not only in our physical appearance but also in the way we move and the way we interact with the surrounding environment. These complexities present challenging obstacles that have driven years of computer vision and deep learning research, some of which will be discussed in this article.

Modeling Humans

Our first objective is to formulate an effective representation of the human body. The initial question we may ask ourselves is: what are the defining points of our body? You might come to the realization that our joints are quite capable of expressing our body pose. This paradigm of modeling humans as a collection of joints has long been established

But are joints sufficient in modeling diverse humans? Sure, joints capture our primary body structure, but it neglects the detailed shape of our body. After all, we aren’t just a collection of dots. It’s the manner in which our body mass is shaped and distributed that is responsible for the diversity in our appearances. Most importantly, we must realize that the surface of our body, our skin, is what is perceived by the world and is what interacts with the environment. This makes it all the more necessary to come up with a representation that encapsulates these attributes.

SMPL

Given the modern context of machine learning, our intuition will likely point us towards constructing a parameterized model. This model should (1) take as input a certain set of parameters encoding the body pose and shape and (2) output a surface vertex mesh. In this section, we’ll explore a foundational statistical model that satisfies this criteria, known as SMPL or Skinned Multi-Person Linear model

SMPL holds several properties that greatly simplifies learning. At its core, SMPL’s objective is to parameterize deviations from a template mesh \(T\) rather than the entire mesh itself, making it much easier to optimize. It is also a factored and additive model, meaning that body shape and pose are independent and their aggregated deviations determine the final result.

Let’s take a closer look at the parameters. We can define the pose parameters \(\vec{\theta} \in \mathbb{R}^{3K + 3}\) as rotation vectors encoding the root and joint orientations. Note that these rotations are relative to the template pose. On the other hand, the shape parameters \(\vec{\beta} \in \mathbb{R}^{10}\) are derived from the data’s distribution of body meshes. Each mesh is made up of tens of thousands of vertices, which poses a problem because each body shape is a point in this high-dimensional space. To combat this, we can apply dimensionality reduction methods like principal component analysis to obtain a more efficient representation. Recall that the top principal components are responsible for the majority of body shape variance within the training data. It follows that we can view each element of \(\vec{\beta}\) as a descriptor for different aspects of one’s body shape (e.g. height).

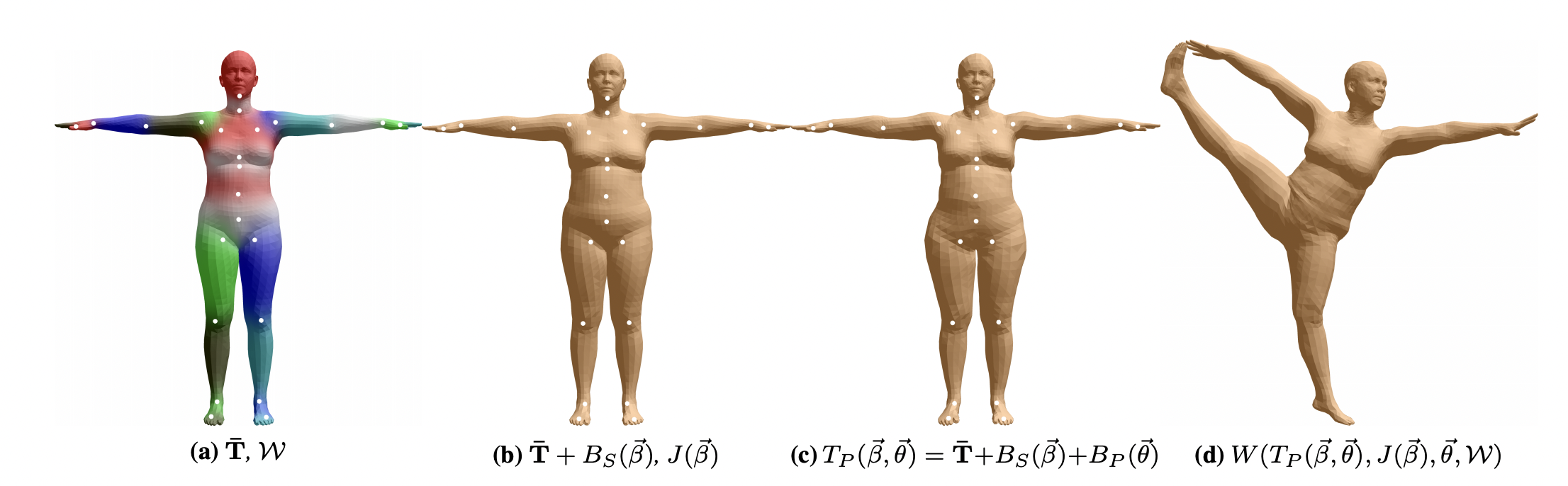

With these parameters in mind, we can begin to understand the high-level details of the SMPL pipeline. For any person, we start with an initial artist-made mesh with \(N = 6890\) vertices and \(K = 23\) joints. This starting mesh is in the mean template shape \(T \in \mathbb{R}^{3N}\) and in its rest pose \(\vec{\theta}^*\). Using the shape parameters \(\vec{\beta}\), we can compute corresponding vertex displacements using a blend shape function \(B_S (\vec{\beta}): \mathbb{R}^{\\|\vec{\beta}\\|} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{3N}\), which essentially represents how far away the subject shape is from the mean template shape. Moreover, the shape parameters are used in the joint location prediction function \(J(\vec{\beta}): \mathbb{R}^{\\|\vec{\beta}\\|} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{3K}\) to compute the location of the \(K\) joints. So, \(T + B_S (\vec{\beta}), J(\vec{\beta})\) encapsulates the subject’s shape in rest pose. Now, we include the pose parameters \(\vec{\theta}\) with a pose-dependent blend shape function \(B_P (\vec{\theta}): \mathbb{R}^{\\|\vec{\theta}\\|} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{3N}\), which accounts for the subject’s pose-dependent deformations. This deformation-adjusted subject mesh is expressed as \(T_P (\vec{\beta}, \vec{\theta}) = T + B_S (\vec{\beta}) + B_P (\vec{\theta})\). It remains to obtain the final posed and shaped mesh. This can be done with a standard blend skinning function \(W(T_P (\vec{\beta}, \vec{\theta}), J(\vec{\beta}), \vec{\theta}, \mathcal{W}): \mathbb{R}^{3N \times 3K \times \\|\vec{\theta}\\| \times \\|\mathcal{W}\\|} \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^{3N}\), where \(\mathcal{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times K}\) is a set of blend weights.

We can utilize the base SMPL model with the smplx library.

from smplx import SMPLLayer

from smplx.lbs import vertices2joints

smpl = SMPLLayer(model_path="smpl", gender='neutral')

smpl_output = smpl(body_pose=body_pose,

global_orient=global_orient,

betas=betas,

transl=transl)

verts = smpl_output.vertices

joints = vertices2joints(smpl.J_regressor, verts)

Here, the body_pose correspond to the pose parameters \(\vec{\theta}\). Both body_pose and global_orient are in rotation matrix form, meaning that it takes on the shape \((..., 3, 3)\). The betas are shape parameters \(\vec{\beta}\) of size \((..., 10)\). transl is then a \((..., 3)\) vector describing the subject’s global translation. The mesh vertices can be obtained with smpl_output.vertices and we can convert these vertices to joints using the joint regressor smpl.J_regressor.

Human Pose Estimation

Great! Now that we’ve seen the expressive capability of SMPL, we can put it to use! You can imagine scenarios like autonomous driving, where we’d like our deep learning models to estimate agent poses within the scene given raw images. Being able to extract SMPL meshes from unconstrained images can provide rich context for downstream autonomy tasks.

One approach, SMPLify

Specifically, this is composed of

- \(E_{\text{J}} (\vec{\beta}, \vec{\theta}; K, J_{est})\) – a displacement error between the pseudo ground truth joint locations and the estimated SMPL joint locations after projection

- \(E_\theta (\vec{\theta})\) – a term to encourage predicting more probable poses by approximating a pose distribution with a gaussian mixture model

- \(E_{\text{a}} (\vec{\theta})\) – a penalty term for unnatural elbow and knee rotations, quantified by \(\sum_i \exp(\theta_i)\)

- \(E_{\text{sp}} (\vec{\theta}; \vec{\beta})\) – a penalty term for interpenetration

- \(E_\beta (\vec{\beta})\) – a shape prior term defined as \(\beta^{T} \Sigma_{\beta}^{-1} \beta\), where \(\Sigma_{\beta}^{-1}\) are the squared singular values from applying PCA on the dataset

Motion Recovery

We’ve successfully modeled humans with

Recall that SMPLify uses an intrinsic camera matrix \(K\) to regress projected SMPL joints, meaning that the fitted SMPL mesh will lie in the provided frame’s coordinates. Now consider the case where the camera moves with each frame. An issue arises because the resulting SMPL meshes will not be contained in a unified coordinate system, so the sequence of meshes would not capture the true motion. Another point to examine is the computational inefficiency with frame-wise processing. We would prefer a method that can output all meshes in one go.

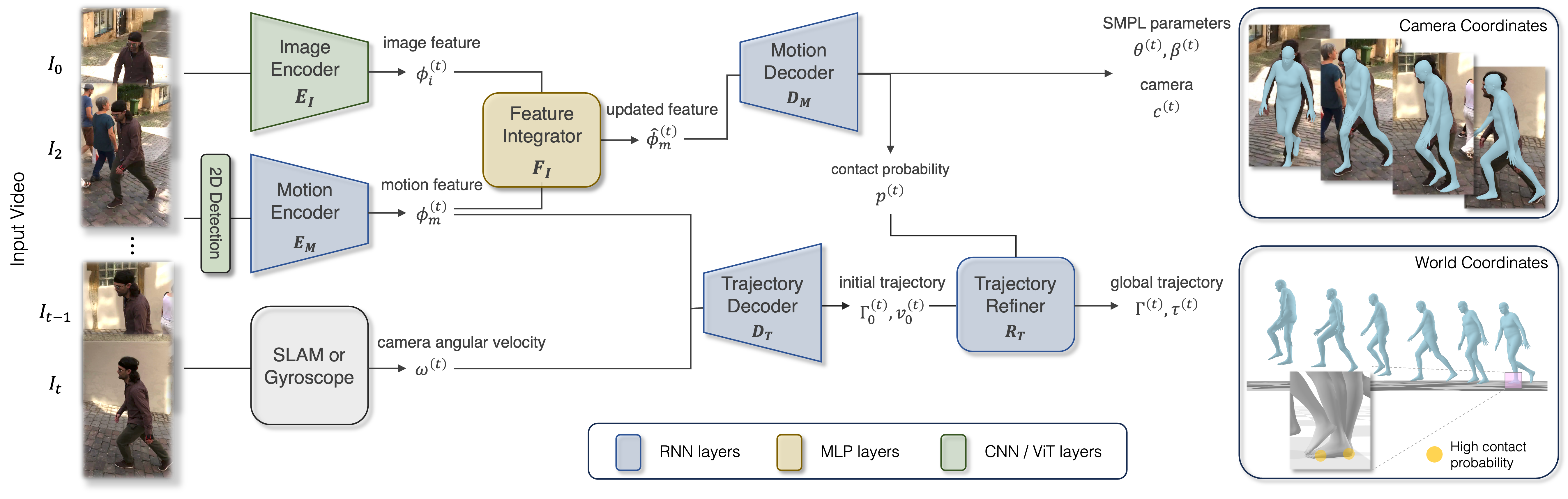

WHAM

One such method is WHAM or World-grounded Humans with Accurate Motion

With this tool at our disposal, we can now (1) compute motions in a consistent global coordinate system, (2) do so with computational efficiency, (3) recover natural-looking motions with foot-ground contact, and (4) capture motions with an arbitrary moving camera

Generating Motions

So far what we’ve accomplished is human pose estimation and motion recovery. We’re able to extract SMPL meshes from raw images, which can enhance deep learning algorithms in their ability to reason about the given scene. It turns out, we can take one step further and accomplish motion generation. Why might this be useful? Take the case of autonomous driving once again. Autonomy algorithms rely immensely on a abundant supply of data to train on. Despite recent advances in data collection procedures, it remains difficult and expensive to aggregate data on a large-scale. In particular, physical constraints pose a bound on the quantity and diversity of collected data. However, with motion generation, we can provide models with a plethora of data that, although synthetic, can be created comparatively with ease and has the potential to introduce greater diversity. We see this simulation approach used quite frequently, especially in reinforcement learning, where policy evaluation would be impossible if done in a physical environment. You might be rightfully concerned with the inevitable distribution shift between synthetic and real-world data. Bridging the gap between real and simulation is indeed still an active area of research, but has seen promising developments due to recent directions in generative AI.

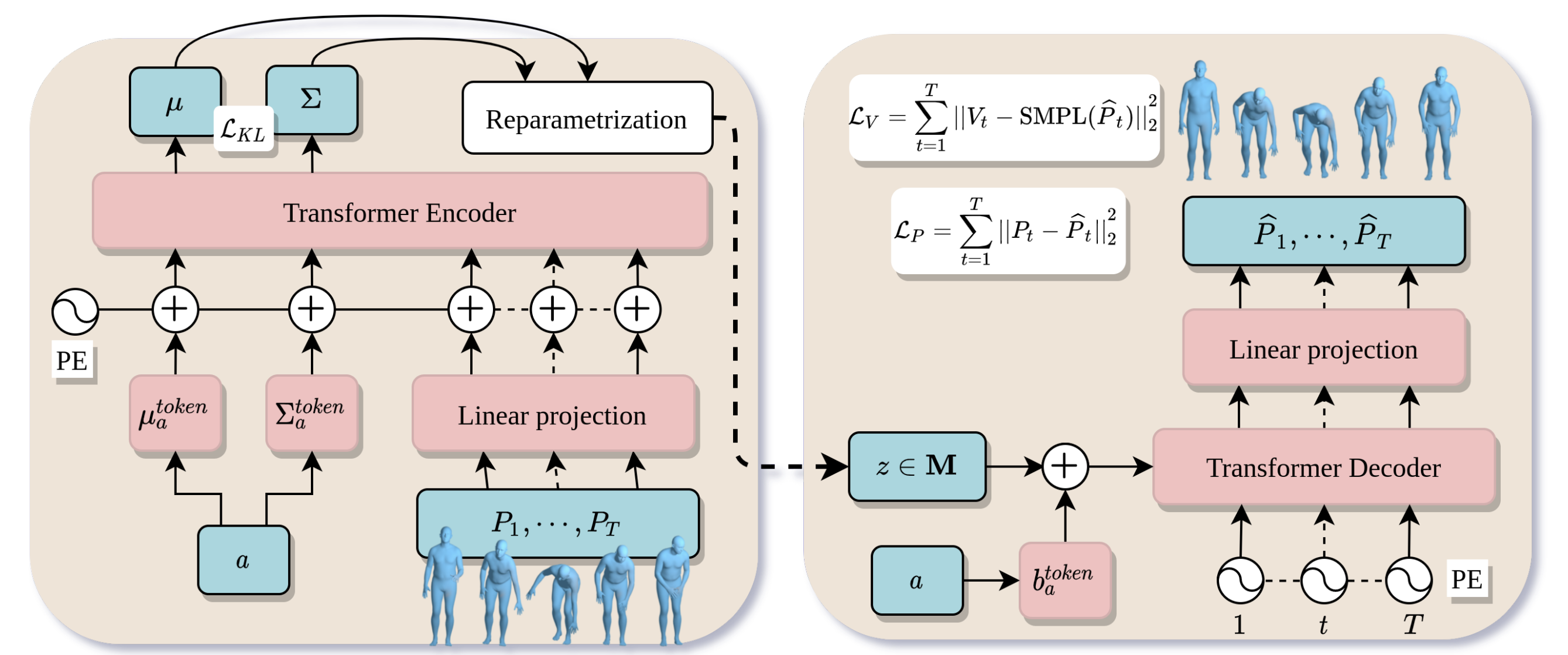

So, we are inclined to devise a framework for motion generation. For this, we can borrow ideas from image generation. One popular paradigm is the VAE or variational autoencoder. To train VAEs, input images \(x \in \mathbb{R}^{N}\) are first passed into a probabilistic encoder, outputting a distribution over a lower-dimensional latent space. Then, a latent vector \(z \in \mathbb{R}^{M}\) is sampled and passed into a probabilistic decoder, producing a distribution over the image space. A reconstructed image can then be sampled accordingly. We omit the proof here, but it can be proved that VAEs can be optimized with the evidence lower bound. We can directly adopt this setup, where instead of having an image distribution as the input, we have a distribution over motions, represented by SMPL parameters. ACTOR

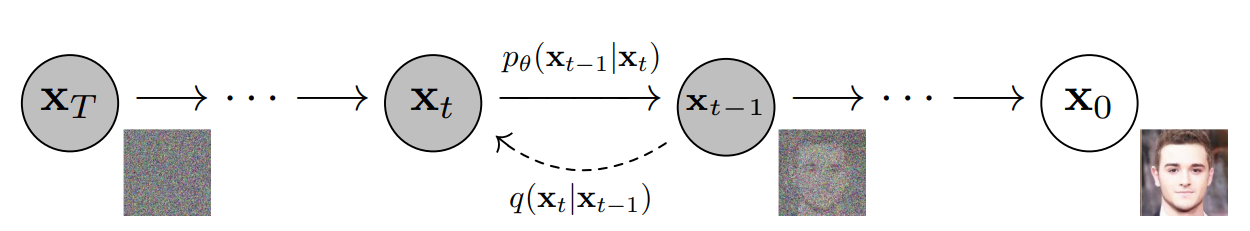

Of course, most recently, a new paradigm has exploded in popularity, namely diffusion models. In this setup, an input image is gradually diffused by injecting random gaussian noise until the image asymptotically converges to \(\mathcal{N}(0, \bf{I})\). In its most basic design, the goal of a diffusion model, then, is to learn a reverse diffusion process that gradually denoises this random vector back to a recognizable image, hence the name denoising diffusion probabilistic models or DDPM

Using the same idea, we can construct motion diffusion models

Click here for a mathematical review of diffusion models. (from Jonathan Kao’s ECE 239AS: Deep Learning and Neural Networks and

The entire forward diffusion process with \(T\) time steps can be expressed as follows:

\[q(x_{0}, ..., x_{T}) = q(x_{0}) \prod_{t = 1}^{T} q(x_{t} \vert x_{t - 1})\]where \(q(x_{t} \vert x_{t - 1}) = \mathcal{N} (\sqrt{1 - \beta_{t}} x_{t - 1}, \beta_{t} \bf{I})\).

We can derive a closed form expression for \(q(x_t \vert x_0)\) by linearity of normal distributions. In the following derivation, define \(\bar{\alpha}_{t} = \prod_{t = 1}^{T} \alpha_{t}\) and \(\epsilon \sim \mathcal{N} (0, \bf{I})\).

\[\begin{aligned} x_{t} &= \sqrt{1 - \beta_{t}} x_{t - 1} + \sqrt{\beta_{t}} \epsilon \\ &= \sqrt{\alpha_{t}} x_{t - 1} + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_{t}} \epsilon \\ &= \sqrt{\alpha_{t}} (\sqrt{\alpha_{t - 1}} x_{t - 2} + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_{t - 1}} \epsilon) + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_{t}} \epsilon \\ &= \sqrt{\alpha_{t} \alpha_{t - 1}} x_{t - 2} + \sqrt{\alpha_{t} (1 - \alpha_{t - 1})} \epsilon + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_{t}} \epsilon \\ &= \sqrt{\alpha_{t} \alpha_{t - 1}} x_{t - 2} + \sqrt{1 - \alpha_{t} \alpha_{t - 1}} \epsilon \\ &\dots \\ &= \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t}} x_{0} + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t}} \epsilon \end{aligned}\]Thus, \(q(x_{t} \vert x_{0}) = \mathcal{N} (\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t}} x_{0}, (1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t}) \bf{I})\).

Given \(p_{\theta} (x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t}) = \mathcal{N} (\mu_{\theta} (x_{t}), \Sigma_{\theta} (x_{t}))\), we need to derive a loss function, such that we maximize the likelihood of \(x_{0}\) under \(p_\theta\). This is equivalent to minimizing the negative log likelihood.

\[\begin{aligned} -\log p_{\theta} (x_{0}) &= \mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})} [-\log p_\theta (x_{\theta})] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})} [-\log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{0:T})}{p_{\theta} (x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})}] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})} [-\log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{0:T})}{p_{\theta} (x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})} \frac{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})}{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})}] \\ &= \mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})} [-\log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})}] - \underbrace{\mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})} [\log \frac{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})}{p_{\theta} (x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})}]}_{D_{KL} (q \| p) \geq 0} \\ &\leq \mathbb{E}_{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})} [-\log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})}] \end{aligned}\]We have now arrived at the evidence lower bound or ELBO, which tells us that we can minimize the negative log likelihood by minimizing the bounding expectation term. We can continue to simplify this expression.

\[\begin{aligned} -\log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{0:T})}{q(x_{1:T} \vert x_{0})} &= -\log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{T}) \prod_{t = 1}^{T} p_{\theta} (x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t})}{\prod_{t = 1}^{T} q(x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t}, x_{0})} \\ &= -\log p_{\theta} (x_{T}) - \sum_{t = 1}^{T} \log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t})}{q(x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t}, x_{0})} \\ &= -\log p_{\theta} (x_{T}) - \log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{0} \vert x_{1})}{q(x_{1} \vert x_{0})} - \sum_{t = 2}^{T} \log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t})}{q(x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t}, x_{0})} \\ &= \log \frac{q(x_{T} \vert x_{0})}{p_{\theta} (x_{T})} - \log p_{\theta} (x_{0} \vert x_{1}) - \sum_{t = 2}^{T} \log \frac{p_{\theta} (x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t})}{q(x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t}, x_{0})} \end{aligned}\]After further derivations, we will end up with the following KL-divergence term.

\[-\sum_{t = 2}^T \mathbb{E}_{q(x_{t} \vert x_{0})} [D_{KL} (q(x_{t} \vert x_{t - 1}, x_{0}) \| p_{\theta} (x_{t - 1} \vert x_{t}, x_{0}))]\]Because \(q(x_{t} \vert x_{t - 1}, x_{0})\) is a gaussian distribution, we just need to compute its mean and variance, which turns out to be:

\[\begin{aligned} \mu_t &= \frac{\sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t - 1}} \beta_{t}}{1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t}} x_{0} + \frac{\sqrt{\alpha_{t}} (1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t - 1})}{1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t}} x_{t} \\ \sigma_{t}^{2} &= \frac{\beta_{t} (1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t - 1})}{1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t}} \bf{I} \end{aligned}\]We can now write out the KL-divergence term and obtain an objective function that is a scaled squared error between the means of the two gaussians. This can be further simplified, using the expressions derived above, to a squared error between the predicted noise \(\epsilon_{\theta}\) and the true noise \(\epsilon\).

We’d like \(x_{0}\) to represent our full motion vector, which should have the shape \((B, T, D)\), where \(B\) is the batch size, \(T\) is the number of frames, and \(D\) is the number of input features. To determine the value of \(D\), recall that each SMPL mesh is represented by (1) joint rotations \(\in \mathbb{R}^{23 \cdot 6}\), (2) global rotation \(\in \mathbb{R}^{6}\), (3) global translation \(\in \mathbb{R}^{3}\), and (4) body shape parameters \(\in \mathbb{R}^{10}\). Thus, we have \(D = 23 \cdot 6 + 6 + 3 + 10\). Note that we use the matrix form for rotations rather than the axis-angle equivalent.

There’s a couple adjustments that we can make based on intuition and empirical results. Because of the sequential nature of our temporal input, we can utilize a transformer-based architecture instead of a U-Net to obtain better performance. Another observation is that a person’s body shape does not change within the timeframe of a single motion, so we should treat it as a prior instead of an input feature to promote training stability (\(D\) is now \(23 \cdot 6 + 6 + 3\)).

In the end, we can optimize our transformer-based denoising model by taking gradient steps on \(\nabla_{\theta} {\left \lVert \epsilon - \epsilon_{\theta} (x_{t}, t) \right \rVert}^{2}\), where \(x_{t} = \sqrt{\bar{\alpha}_{t}} x_{0} + \sqrt{1 - \bar{\alpha}_{t}} \epsilon\).

Next, it’s important to consider potential evaluation metrics to determine our model’s performance. One metric we can compute is the mean per joint position error or MPJPE between the generated and ground truth motions. Although this metric is primarily used for motion estimation, it can help quantify how reasonable and realistic the generated motion is. We can also calculate a average displacement error or ADE, which is the temporal average of the \(\mathcal{l}_2\) distance from the ground truth as well as a final displacement error or FDE, which reflects the deviation of the generated motion’s final position from the ground truth. Diversity metrics can be used to indicate the variety of generated motions.

Controllable Generation

At this point, we’ve designed a diffusion model that can generate human motions unconditionally. But, in most cases, we have some criteria for the type of motions to generate, whether that be some label, text prompt, or visual scene context. How do we modify our diffusion model to consider these conditions?

To start, we can directly add a conditioning signal as an input to our denoising model. However, we would soon realize that this approach lacks robustness, as the signal will oftentimes be ignored by the model. We want a method that gives us more control over the conditioning effect.

Thus, we can amplify the effects of our conditioning signal by applying a guidance scale \(\gamma\) on \(\nabla \log p(y \vert x_{t})\). This will give us much better sampling results, but there still remains some drawbacks. It’s difficult to obtain a suitable classifier, since it must be capable of classifying noisy inputs \(x_{t}\). Another problem is that when it comes to conditioning on text prompt or visual context, there’s no notion of classification.

To solve our problem, we can use classifier-free guidance

This result tells us that we no longer need an additional classifier. It suffices to have an unconditional diffusion model \(p(x_{t})\) and a conditional diffusion model \(p(x_{t} \vert y)\). We can obtain both of these with a single denoising model, by zeroing out the conditioning signal randomly during training with probability \(p_{\text{uncond}}\)

Awesome! We have a conditional diffusion model that can generate realistic human motions given a text prompt. And through this, we’ve obtained controllability with generation. But wait… there’s more to be done.

First off, the approach we have taken with diffusion models restricts us to generating motions of fixed length \(T\). Naturally, we can try to generate arbitrarily long motions through autoregressive generation of shorter, fixed-length motion sequences, but let’s see if we can leverage diffusion itself to overcome this obstacle.

Currently, independently generating two motions and concatenating them together will result in unrealistic and rough transitions. So, how can we refine this transition segment motion, so that it appears more natural and logical?

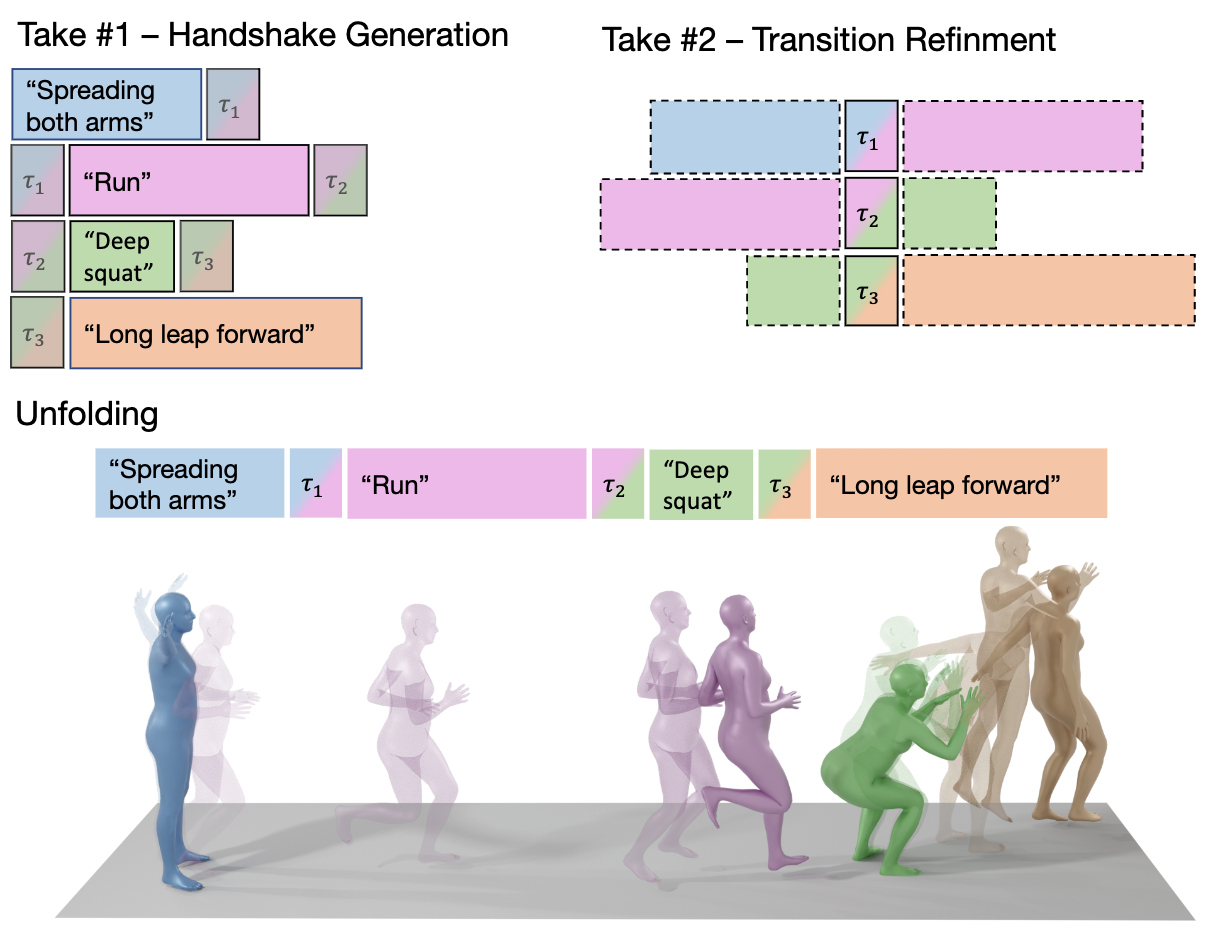

In the first take, short-term motion intervals are generated independently as a batch. A handshake is then maintained at each denoising step, where the transition segments are replaced with the frame-wise average of the corresponding motion prefixes and suffixes. This ensures a certain extent of consistent generation between intervals. The update equation is as follows:

\[\tau_{i} = (1 - \vec{\alpha}) \odot S_{i - 1} [-h:] + \vec{\alpha} \odot S_{i} [:h]\]\(S_{i - 1} [-h:]\) is the suffix of the preceding motion and \(S_{i} [:h]\) is the prefix of the succeeding motion. \(\alpha_j = \frac{j}{h}\) for all \(j \in [0, h)\). Note that \(\odot\) is the hadamard product.

The second take enhances the smoothness of transition segments by noising a soft-masked interval for some \(T'\) steps and denoising it to a clean motion.

Besides long-term motion generation, we often desire to generate movements given some motion criteria, such as its trajectory. Such a task is known as motion inpainting, which is analagous to image inpainting. Instead of filling in unknown pixels, we’re using motion priors to generate the rest of the motion vector. A common technique is to impute noised target motion values after every denoising step \(t\). The imputed sample can be expressed as

Here, \(y_{t - 1}\) are the noised target values we want to impute on the noised motion vector \(x_{t - 1}\). This could, for instance, be the noised motion trajectory. \(M_{y}^{x}\) is a mask denoting the imputation region of \(y\) on \(x\) and \(P_{y}^{x}\) is a projection of \(y\) to \(x\) that resizes \(y\) by zero-filling. However, applying imputation this way may not be as effective as it seems.

Closing Thoughts

Hopefully this article gave you a glimpse of the incredible work that has already been done to effectively represent and generate human motion. The field continues to rapidly expand to new areas, such as multi-person motion generation and human-object interaction synthesis. It’s exciting to see where research will take us next!